This is a long read, so here’s the short version: In 2012, some problems came to light in three papers with a common author. One journal retracted the paper, albeit after much effort and with an opaque retraction notice. Another acknowledged the problems but refused to act and is now incommunicado. At the third journal there is reason to suspect an investigation may have been compromised by conflict-of-interest. Combined, these events do not speak highly to the manner in which journals handle these affairs. What’s more COPE guidelines appear to encourage such practices. Oh, and just to complicate things, the author of the papers threatened to sue me. There is no happy ending.

Disclaimer and motives: I can’t get into the potential reasons why the data in these papers appear the way they do. All I can do is report on what’s out there in the public domain, and offer my own (first amendment protected) opinion about why these images appear odd to me. It should also be clear that in discussing these papers, I’m not drawing any parallels to online discussions that may have happened about them in the past. The opinions expressed here are my own (***see also bottom of page).

So why do this? Well, I don’t like mistakes, and assuming everything I’m about to show you is the result of honest mistakes, that means: (i) journals are not doing their jobs as gatekeepers of reliable scientific information, (ii) people are not proof-reading their manuscripts before submission, and (iii) poor data management is being rewarded with grants, publications and career advancement. Because success in academic science is a zero sum game, when people who make mistakes get ahead, others are deprived of success. That’s not fair.

How it started: Alleged problems in the data of three papers from Gizem Donmez at Tufts University came to light in fall 2012:

J. Neurosci. 2012;32;124-32; PMID22219275

J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287;32307-32311; PMID22898818

Cell 2010;142;320-332; PMID20655472

The problems appeared to involve undisclosed splicing together of western blot images, and in some cases apparent re-use of western blots (or portions thereof) across different figures. Detailed descriptions are available at PubPeer (J Neurosci / J Biol Chem / Cell) for those interested. I have been involved for over a year in trying to ensure the journals deal with these alleged problems appropriately. What follows is a summary of what happened in each case. (Note – some email content is redacted for brevity, but full transcripts can be provided on request)…

What happened at J. Neurosci. 7 months after my initial contact, Editor-in-Chief John Maunsell responded:

The SfN requested institutional investigations […] institutions produced detailed reports that included the original images used to construct the figures. The images clearly documented that the figure elements that appeared to be replicates in the article in J. Neurosci. were in fact from different gels. Because there was no evidence that any results had been misrepresented, the SfN has dismissed the case. We consider the matter closed.

I protested, asking why the issue of undisclosed splicing was not resolved. I also questioned whether the journal had actually seen the originals or was simply relying on the institutional report? This was the response:

Your concerns about the spliced gels did not escape our attention. We did not take action for two reasons. First, the image manipulation policy of J. Neurosci. was only instituted in December 2012, after this article was published. While it is regrettable that we did not have a more rigorous explicit policy in place sooner, we cannot impose retroactive policies on published articles. Second, while the spicing misrepresented details of the experiment design, the institutional investigations left us with no reason to believe they misrepresented any of the scientific findings of the study. While there are good reasons why authors should not manipulate images in this way, the figures appear to faithfully reproduce the results obtained, and would not impede anyone from replicating the author’s results. Because none of the scientific finding were represented, a correction would provide no value for readers of the article.

Refusing to retroactively apply a policy that every other journal had in place years ago, seems rather odd, as does the assertion that a correction would provide no value. Anyway, I let it go for a while then wrote back again in fall 2013, notifying that the JBC paper had been retracted (see below), and the lead author had threatened to sue me. The journal responded:

We are unprepared to reopen this case. The events surrounding other publications and your interactions with Dr. Donmez are immaterial for this matter. Your assertion […] is misguided. I acknowledged these images look very similar, but the institutional investigation included examination of the original, high-resolution, uncropped images, and the material presented to us** showed the similarity was a remarkable coincidence. I understand that you and others will find that surprising, but there is no arguing with the originals. We consider this matter closed.

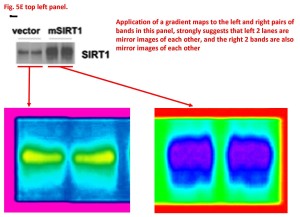

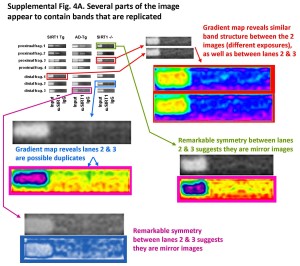

** It is unclear if the journal has actually seen the originals, or is merely relying on what has been been presented to them by the institution. So I wrote back again, this time documenting a further analysis of the data, including the following images:

While it’s technically feasible those images originated from different experiments, it would represent a remarkable coincidence! Maybe I should go buy lottery tickets right now? Anyway, it doesn’t matter because the journal didn’t respond to my email. Four months later they’re still ignoring me.

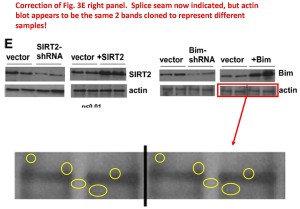

What happened at J. Biol. Chem. JBC‘s dedicated ethics officer Patricia Valdez has been a model citizen for interactions with readers and forwarding the journal’s agenda of increased transparency. That being said, things got interesting in May 2013 when JBC published a correction to the questioned paper. The correction acknowledged that some western blots in the paper were subjected to splicing, and replacement figures were provided with splicing seams clearly indicated by solid lines. The correction stated that the splicing “in no way affects the conclusions of the paper or the original interpretation of the results”. If only it were that simple…

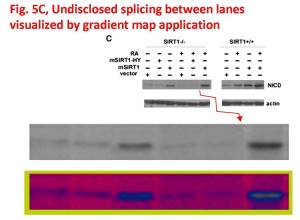

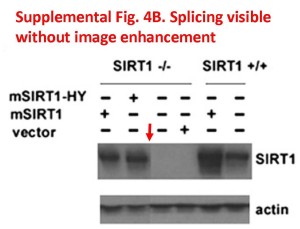

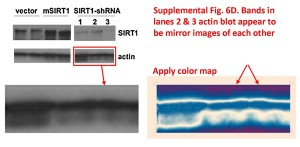

Straight away it came to my attention that, while acknowledging the splicing, the correction failed to address the issue that images on each side of the splicing seams appeared similar. So, I wrote to JBC with a detailed analysis of the corrected images, including the following:

After walking Ms. Valdez through the images in a ‘phone conversation, she agreed that things deserved another look. She also indicated by email that the initial decision to correct was based on an institutional report (sound familiar?). After several follow-up communications the journal issued a retraction notice on July 24th 2013. Here’s the full text of that notice:

This article has been withdrawn by the authors

Move along, nothing to see here! I won’t speculate on the reasons why JBC broke protocol and permitted an opaque notice. However, I will note that this occured on the same day as Dr. Donmez threatened to sue me. In addition Diane Souvaine (Dean at Tufts) stopped answering my emails around the same time.

What happened at Cell. The journal didn’t respond to my original contact in fall 2012, so I tried again in fall 2013 (yes thank-you I have a day job that keeps me busy, hence the delay). In my email I emphasized the importance of avoiding conflict-of-interest, because the senior author on the Cell paper (Leonard Guarente at MIT) sits on the editorial board of the journal. A week later, Editor-in-Chief Emilie Marcus responded that they’d look into it. Nothing was heard for 2 months, then last week I received the following email:

Dear Dr. Brookes,

Thank you for your e-mails. In addition to having been informed of the results of the institutional investigation, we have also examined the implicated figure panels editorially. Despite some apparent superficial similarities, upon extensive examination we were unable to find any compelling evidence for manipulation or duplication in those panels and therefore are not taking any further action at this time.

Best wishes,

Sri Devi Narasimhan, PhD, Scientific Editor, Cell

Having not seen the name before, I looked into the background of Dr. Narasimhan. It turns out she came from the lab’ of Heidi Tissenbaum at UMass. Guess where Dr. Tissenbaum did her post-doc! Can you say conflict-of-interest?

Despite being specifically warned about conflict, Cell put someone who is a scientific descendent of the lead author in charge of the investigation. The response also offered no details on the tools used to reach these conclusions, and no mention whether original images were requested. Furthermore, the response fails to address undisclosed splicing.

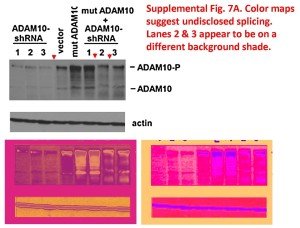

I responded, raising these issues and CC’ing the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). Despite additional ‘phone calls and even leaving my cellphone number, a week later I’ve received no response from Cell. So, in the interests of completeness, here’s another look at the data, plus a few more apparent problems I found along the way…

Cell hasn’t seen this re-analysis yet, so there’s no word on whether they’ll re-open this case after reading the above. I’ll update if that changes.

What does (the) COPE say? I’m generally a fan of the Committee on Publication Ethics, although they don’t seem to have strong enough teeth to get journals to behave. In response to being CC’ed on my email to Cell, they replied:

Thank you for your email and telephone call […] COPE cannot investigate individual cases but we do hear concerns about member journals. More information and how to follow this process can be found here.

At the link, I learned that official complaints must state which part of the COPE code of conduct has been breached. In that code, editors are advised to “inform readers about steps taken to ensure submissions from members of the […] editorial board receive an objective and unbiased evaluation”. The Cell case appears to be a breach of code, but requiring a formal complaint to be filed places an unnecessary burden on the reader (me). Why cant COPE simply act on the evidence they’ve already received?

Furthermore, COPE guidelines for editors to handle such issues recommend deference to the authors’ institution for a full investigation. If the institution says OK, the journal should run with it. This policy ignores any potential conflict-of-interest at the institution itself (e.g., indirect costs on faculty grants), which to me seems like a rather large hole in the system… Let’s put people who stand to lose big heaps of money in charge, and hope they do the right thing.

What about the legal issue, and what next? In dealing with these papers and the ensuing legal issues, I’ve spent a lot of my own money. That’s money no longer in my kids’ college savings account. I also seriously doubt I’ll be reimbursed by the journals for the significant time I spent doing image analysis – analysis which they should have done during peer review.

There is no happy ending – just a refusal to act, an opaque retraction and a conflicted investigation. Meanwhile, an extremely talented junior investigator from a world-class institution continues to secure high profile grants and, with help from a good lawyer and the powerful Harvard/MIT/Tufts network, is all set for a stellar career. Let’s hope nobody looks at her earlier papers.

_______________

*** If you think anything written above is not a fair representation of the truth, I am open to discussion by email. However, if you wish to challenge the above account, please provide specific evidence to the contrary, not simply opinions/threats.