I just posted a new pre-print reporting on a small investigation in the area of image manipulation and research misconduct. It centers on content from the Journal of Cancer, which is published by the Australian open access publisher Ivyspring.

The TL/DR version is as follows: If your journal does a poor job of screening for garbage pre-publication, it doesn’t really make a difference whether you charge a fee for authors to clean up their own mess.

Charging what now??

One of the notable things about this journal (and others from the same publisher) is that until recently they charged an additional fee for the publication of a correction/erratum to an already published article. Such fees are generally frowned upon by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

Not only could such fees discourage authors from coming forward to correct any problems identified post-publication, it could be hypothesized that they actually create a disincentive for the journal to address problems identified during pre-publication. After all, if you just say nothing and the problem is subsequently found, that’s more sweet revenue for the taking ($AU 1,750 or about $US 1,200 at the time of writing).

In late 2024 the journal abandoned this fee policy, which provides for a convenient way to test a hypothesis. Simply look at the rates of problematic material before and after the policy change, to see if it made any difference to the incidence of problems that need correcting.

ImageTwin-AI to the rescue

Of course, it’s no small undertaking to manually screen hundreds or thousands of papers for problem images. Luckily these days we have AI-assistance tools such as ImageTwin-AI to help with that. There are several such platforms available (including some that are problematic), but ImageTwin is among the best I’ve encountered and has an easy-to-use platform. Previous studies have demonstrated the utility of these platforms in the right hands. FULL DISCLOSURE – I was an early tester for ImageTwin, and so have access to it as a courtesy from the site owners (thanks Markus!)

What was done?

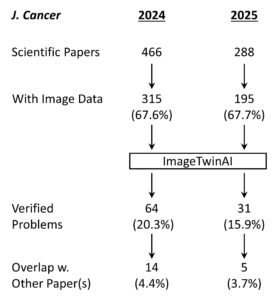

Shown above is the workflow for the study. A total of 754 papers were of the type suitable for screening – meaning they were original scientific papers rather than review articles, editorials, consensus statements or other journal content. Of these, 510 contained image data and were fed into ImageTwin (usually in batches of 4-6 at a time). Every “hit” was manually verified, then annotated in powerpoint to highlight the problem(s).

A number of problem images were flagged by ImageTwin but removed from the analysis. This included the use of IHC and other images from publicly available databases such as the Human Protein Atlas (HPA). Likewise, using the same image to represent the same experimental condition (such as control cells) within a paper cannot really be construed as a huge problem. It’s not best practices, but it’s also likely not misconduct (the exception here is when a single western blot loading control image is used for dozens of blots, which is simply physically impossible).

What was found?

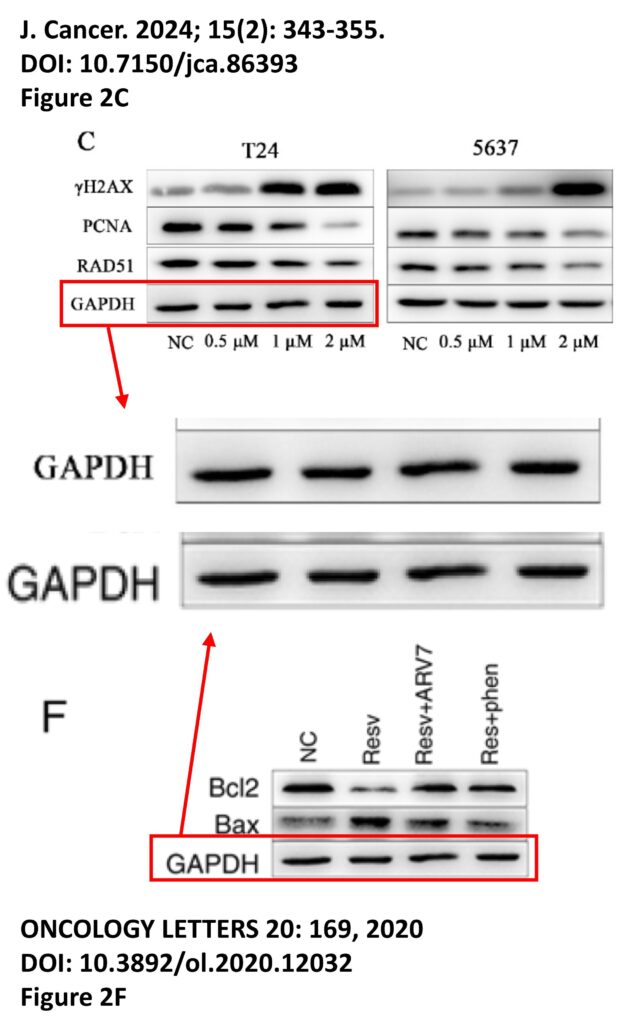

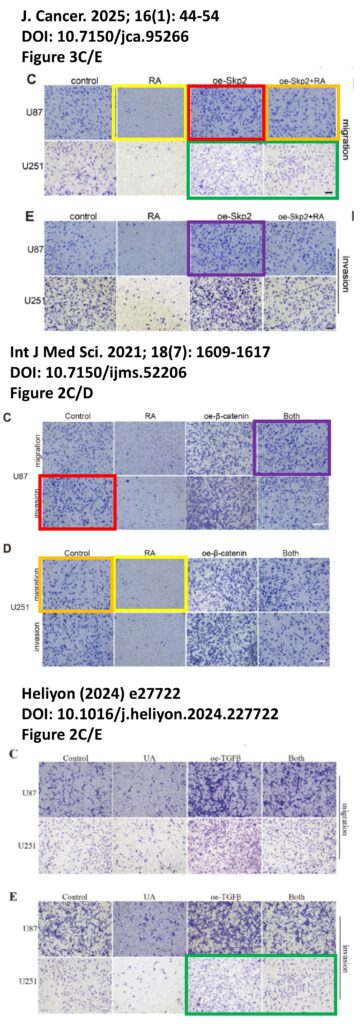

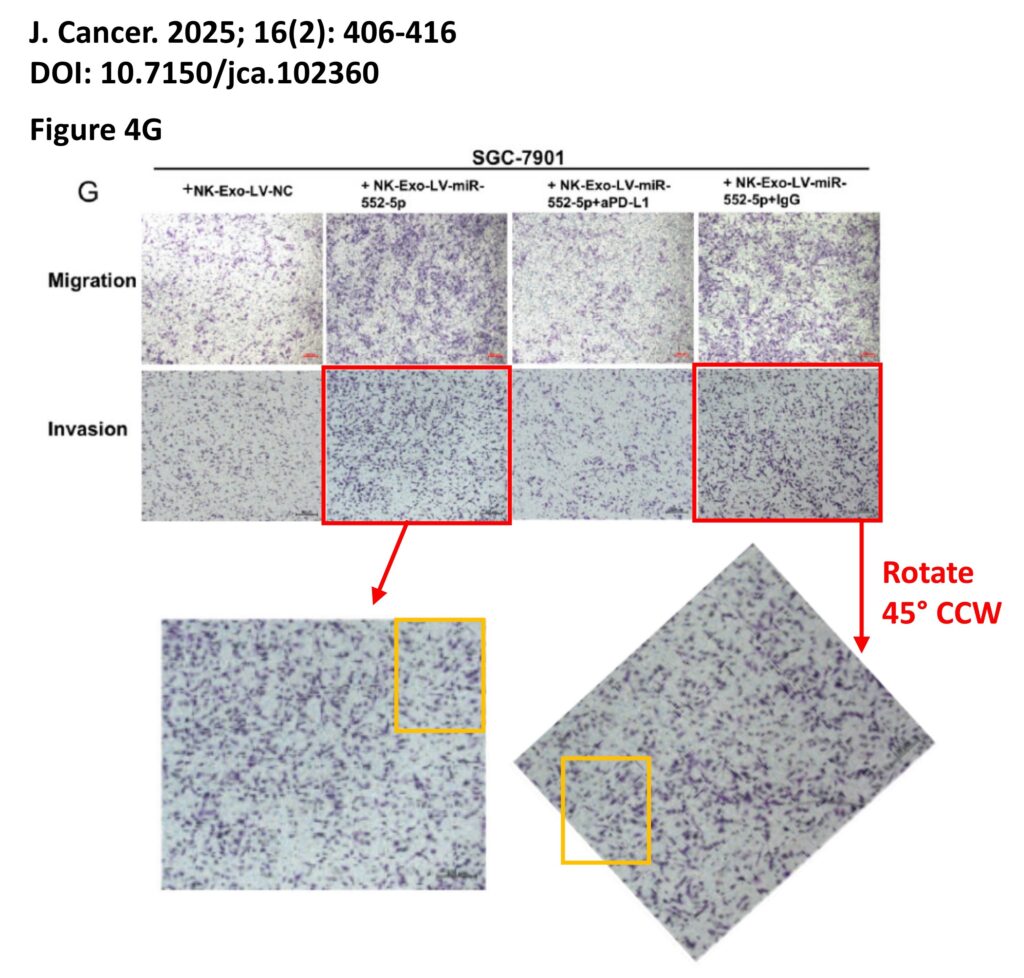

The platform found 95 papers with evidence of inappropriate image manipulation. This included 19 papers with overlapping content from completely unrelated journals or papers. This latter group really is the gold value proposition of ImageTwin – it would have been virtually impossible to find such image matches manually. Here are a couple of examples:

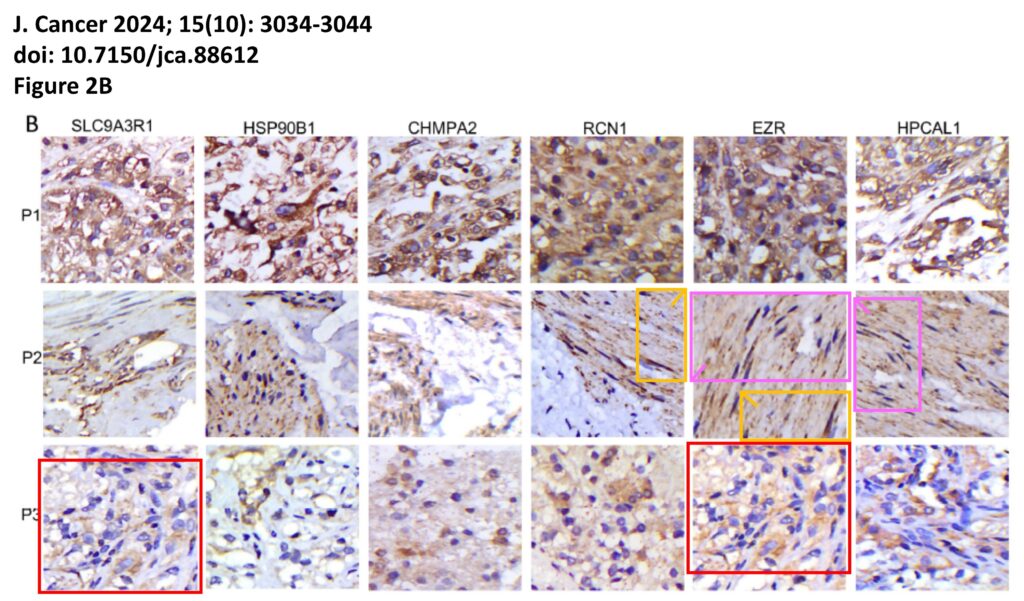

The platform also identified a host of problems within individual papers, such as these…

For those interested, the complete documentation of all problems is available on FigShare, comprising 2 PDFs with the annotated images, plus an Excel spreadsheet detailing the 153 separate examples of image manipulation.

What about the original question?

Overall the fraction of papers with problematic images fell from 20.3% in 2024 (while the correction fee was in place) to 15.9% in 2025 (after the fee policy was rescinded), suggesting only a modest impact on editorial processes at the journal.

Caveats

Of course, there are many caveats to this study, such as the fact it’s from a single journal and only a few hundred papers. It would be interesting to repeat the analysis with other journals from the same publisher, since they all had the same fee-for-correction policy in place until recently.

Another caveat is that of course this data set doesn’t reveal anything that goes on at the editorial level. Who knows why or when the publisher decided to stop charging for corrections? It is notable that COPE re-jigged their guidelines on fees in late 2024, but that may be pure coincidence. Personally, I would consider it highly unlikely that on Jan 1st 2025 the editors woke up and said “hey we’re not charging for corrections any more, so get out there and start flagging more stuff during peer review.” If they did, it wasn’t very effective.

One final caveat is the different sized cohorts of papers, with the 2025 volume of the journal publishing ~38% less content than in 2024. This could have been due to simple external factors such as fewer submissions, as scientific funding around the globe becomes harder to obtain. Or it could be because the journal raised their APC to $AU 4,000. Either way, 16% problem papers is still a big number, and not a lot to be proud about.

What’s Next?

As time permits, I may get around to manually posting each of these items on PubPeer, which is unfortunately not yet an automated process. As with all AI tools, the “Trust but Verify” mantra is critical, hence everything in the paper was manually verified and annotated prior to publication. That’s really #1 on my wish-list for these types of analysis, an auto pipeline to go from discovery to online PubPeer documentation in a single click. It’s hard to reconcile such a process with robust human-in-the-loop verification.

Of course if anyone at the journal is reading this, feel free to pull all the original data files from FigShare (it’s all neatly organized for you) and start retracting the worst examples. And maybe consider a subscription to ImageTwin?

There’s also the “cost” to consider. Not just the monetary cost of screening large numbers of papers, but also the externalities of AI compute, including data centers, water usage, carbon footprint. Plus all the other problems of the genAI industry at large, as explored at length by one of my favorite bloggers, Ed Zitron. Whether any of these platforms will be profitable before they run out of venture capital remains to be seen, but personally I’d rather see AI being used for applications such as this, instead of generating pictures of a cat dressed as Lady Gaga playing the flute while riding unicycle.

Summary

What this study really highlights is the great utility of platforms like ImageTwin-AI for rapidly screening papers and discovering image problems. It would have taken forever to do this manually.

The prevalence of problem images in this cohort of papers (18.6% overall) was similar to a previous study from Sholto David on content from a different journal (which found 16%), and agrees with the contention from James Heathers that “1 in 7 scientific papers are fake.” In particular, the 4% of papers that contained images duplicated from unrelated journals are likely candidates for Paper Mill papers, and warrant further investigation on that front. Hopefully they get retracted ASAP.

Lastly, this study really doesn’t support any kind of causative link between following COPE policies and actually driving out problems from a journal. It takes more than simply signing up to an industry lobby group and paying a membership fee, to cleanse the literature of garbage.